JAMES BEARD FOUNDATION® ANNOUNCES THE 2023 RESTAURANT AND CHEF AMERICA’S CLASSICS AWARD WINNERS

NEW YORK (February 22, 2023) – The James Beard Foundation® announced today the six recipients of its 2023 America’s Classics Award. A Restaurant and Chef Awards category, the America’s Classics Award is given to locally owned restaurants that have timeless appeal and are beloved regionally for quality food that reflects the character of its community.

Each year, the Restaurant and Chef Awards Committee recommends, discusses, votes on, and selects the America’s Classics winners. Six of the twelve Restaurant and Chef regions are included within each Awards cycle, and rotated the next cycle, so that each region is represented every other year. The public may submit recommendations for this category for consideration by committee members. To be eligible for this award, establishments must have been in existence for at least 10 years.

This year’s honorees join the ranks of more than 100 restaurants across the country that have received the Award since the category was introduced in 1998. They will be celebrated at the James Beard Restaurant and Chef Awards ceremony on Monday, June 5, 2023 at the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

“The mission of the James Beard Awards is to celebrate excellence and that means recognizing the incredible work of long-standing restaurants that play such a crucial role in our communities, as our America’s Classics winners do,” said Clare Reichenbach, CEO of the James Beard Foundation. “We are so excited to announce this year’s winners. Congratulations to all!”

The 2023 James Beard Foundation America’s Classics Award winners are:

Texas Region

Joe’s Bakery & Coffee Shop 2305 E 7th St, Austin, Texas Owner: Paula Avila

The Avila family has served Austin’s quickly gentrifying East Austin since 1935, when Sophia DeLa’O operated La Oriental Grocery & Bakery from their home on East 9th Street. The business moved to East 7th Street in 1962 and Joe Avila, with the support of his wife Paula, bought the business and created Joe’s Bakery & Coffee Shop.

Though he didn’t realize it at the time, by bringing his childhood dream to fruition, Joe cemented a legacy through food and hospitality that continues to this day. The colorful Mexican pastries, known as pan dulce, and Tex-Mex family recipes draw large crowds hungry for migas, home-style pork carne guisada, and myriad breakfast tacos on homemade flour tortillas. (The infamous “fried bacon”—the dredging of thick-cut bacon through flour and cooking on the flat top grill—is a masterful touch).

But it’s the service and firm sense of community under the stewardship of three generations of Avila women, led by Joe’s widow Paula, that keeps people coming back again and again. A melting pot of new and old Austin, it is not unusual to find old-timers reminiscing about Austin and sharing their stories and recommendations at the breakfast counter with Joe’s Bakery newcomers. It’s commonplace to encounter voter registration on the front patio.

And despite its own struggles during the pandemic, the restaurant doubled as a general store during the peak of COVID-19, selling toilet paper, paper towels, and other essentials. The neighborhood surrounding Joe’s Bakery and Coffee Shop is undergoing rapid development, but the restaurant remains a gathering place and piece of Austin history for longtime regulars and newcomers alike.

America’s Classics: South Region

La Casita Blanca Villa Palmeras 351 Calle Tapia, San Juan, Puerto Rico Owners: Jesús Pérez Ruiz, Mildred De León, Leonardo Pérez De León, Jesús Pérez De León

In 1980, Jesús Pérez Ruiz opened the doors to Casita Blanca in the Villa Palmeras section of Santurce in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The restaurant represents the traditional Puerto Rican fonda, a casual and affordable family-run locale that serves delicious comfort food. For locals, it’s like stepping into your tía’s or abuela’s house with vintage furniture and colorful tablecloths, evoking feelings of nostalgia and fond memories of family gatherings.

Patrons come from all walks of life—the obrero that works construction, the adventurous tourist, lawyers on an extended lunch break, students from the nearby university, and anyone looking for excellent comida criolla. Everyone is treated with kindness and respect, and since its inception, diners have been welcomed with a sopita del día and bacalaíto fritters with homemade pique (hot sauce).

The menu is written on a chalkboard and always includes favorites like patitas de cerdo (pig’s feet), fricase de pollo, carne guisada, and rice and beans. Each meal ends with a chichaíto, an anise-based digestif. Today, Jesús’s two sons run the restaurant with the same love and dedication as their father.

America’s Classics: Pacific and Northwest Region

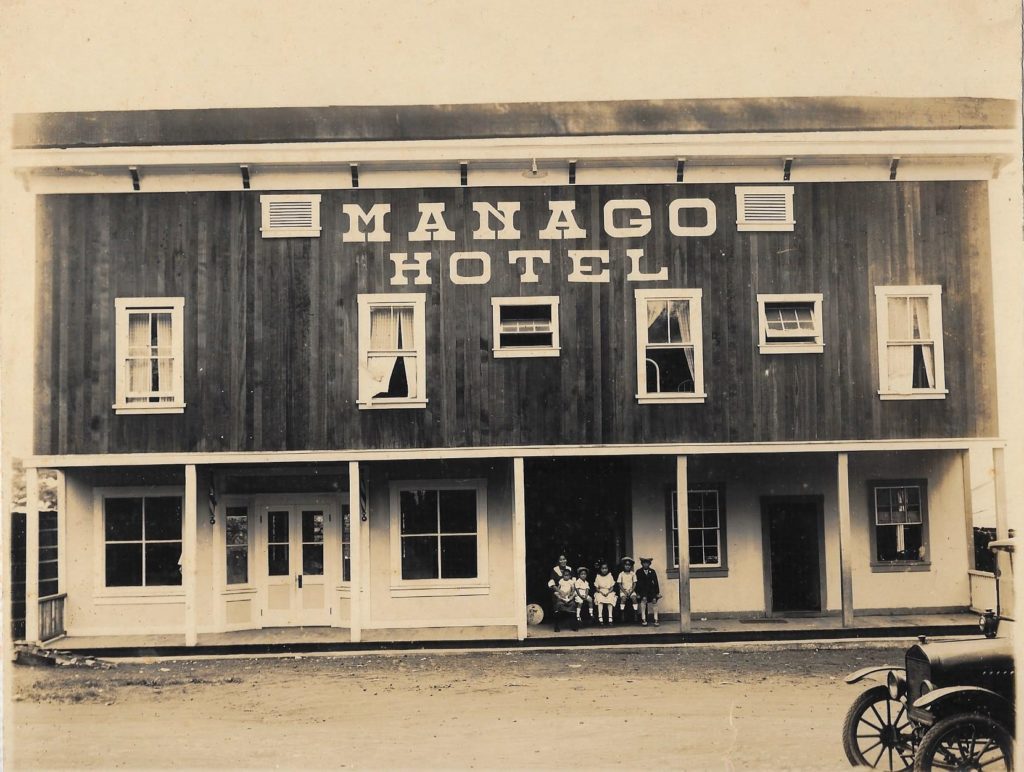

Manago Hotel 82-6155 Hawaiʻi Belt Rd, Captain Cook, Hawai‘i Owners: Britney and Taryn Manago

Manago Hotel is a place that reminds locals of childhood and old Hawai‘i. It is Hawai‘i’s oldest continually operating restaurant—it began in 1917 when Kinzo Manago and his “picture bride,” Osame Nagata, immigrants from Fukuoka, Japan, began selling udon, bread, jam, and coffee out of their home, and then added cots for those traveling between Hilo and Kona.

The hotel and restaurant survived and expanded over the decades, including through World War II, when the Army contracted Manago Hotel to feed soldiers. It’s still a simple place, the rooms have no AC nor TVs, and the restaurant is largely unchanged from the 1940s—from the hand sink by the entrance that the coffee farmers would use before entering, to the pork chops fried in a cast iron pan rumored to be as old as the hotel itself.

The udon and bread are gone, but the menu is still spare, with less than a dozen items, including liver and onions and small local fish such as ‘ōpelu. All entrees come with a large bowl heaped with rice and side dishes on little melamine plates, like Hawai‘i’s banchan, and usually includes potato macaroni salad.

The fourth generation—sisters Britney and Taryn Manago—now run the hotel and restaurant. Britney grew up below the kitchen and had gone to college in California, when homesickness drove her back to the family business. “This is the only thing I’ve ever really known that I’ve loved and wanted to always be a part of,” she says.

America’s Classics: Northeast Region

Nezinscot Farm 284 Turner Center Rd, Turner, Maine Owner: Gloria and Gregg Varney

When Gloria married Gregg Varney, she insisted that they open a café on the farm in Turner, Maine that has been in the Varney family for more than a hundred years. The first organic dairy farm in Maine, Nezinscot Farm takes its name, shared by a nearby river, from the Abenaki word signifying a place to gather.

The Abenaki name is seemingly also a mission for the Varneys. In 1987, Nezinscot opened its Café and Coffee shop, and Gloria’s original vision has since expanded to include a bakery, a fromagerie, and charcuterie. The Café has something beautiful and exciting on every shelf—cases of homemade cheeses and meats, bagels, freshly baked pies, and perfect breads rolling out the kitchen, topped with farm eggs and homemade sausage and cheeses. The energy behind it all feels directed at building community, with delicious homemade everything (even the teas, even the crackers) serving as the vital instrument of creating and sustaining that gathering. The Varneys feed the community in many ways, significantly providing a warm space to gather around food on a farm in the middle of Maine.

America’s Classics: Mountain Region

Pekin Noodle Parlor 117 S Main St, Butte, Montana Owner: Jerry Tam

The Pekin Noodle Parlor, located in Butte, Montana, is the oldest continuously operating Chinese family restaurant in America. Hum and Bessie Yow, the original owners of the Pekin Café and Lounge, opened the restaurant in 1911 with the help of Tam Kwong Yee. The Yows built the building that still houses the restaurant in 1909 as a legal office and mercantile. Two years later, the Yows began serving noodles and created their own version of the Chinese-American dish chop suey that satisfied the yearnings of Chinese immigrants working in the mines and railroads.

The restaurant is located on Butte’s historic main drag. To access the restaurant, the diner climbs a flight of long, steep stairs to arrive on the second floor. Here 17 tables, found in booths separated from each other with orange beadboard partitions, occupy the space that once hosted illicit activities. A front room with windows to Big Sky vistas beyond provides space for large groups while a side bar serves up spirited beverages.

The menu is a time capsule, encapsulating Chinese-American dishes created in a time when authentic ingredients were not available. These dishes were a close approximation of home for the hardworking Chinese immigrants. The lengthy menu of mostly Americanized versions of Chinese food spotlights 16 chop suey varieties.

There’s also barbecue pork, egg rolls, sweet-and-sour pork, pineapple fried rice, chow mein, and noodles in broth and “gravy”—a thickened, soy-based sauce. The meal is finished with fortune cookies brought with the bill.

Great-great-great grandson Jerry Tam has taken over the restaurant from his parents Sharon and Ding K. Tam. Jerry’s father Ding, who purchased the restaurant in the 1950s from his grandfather, was affectionately known as Mr. Wong by the community. His passing at the end of 2020 brought a hundred well-wishers when the nearby alley was renamed Danny Wong Way.

America’s Classics: Great Lakes Region

Wagner’s Village Inn 22171 Main St, Oldenburg, Indiana, Owner: Dan Saccomando

For generations, Kentucky’s fried chicken tradition has overshadowed neighboring southeastern Indiana’s. Blame Colonel Sanders—who was, in fact, a native Hoosier. Some of the best fried chicken in the Midwest sizzles in cast-iron skillets at Wagner’s Village Inn in Oldenburg, population 674, otherwise known for its German-American history and its historic churches.

The elements of the fried chicken at Wagner’s are as unpretentious as the wood-paneled dining room: chicken, salt, pepper, flour, lard. There is no recipe. But, as in other southeastern Indiana kitchens, the cooks are heavy-handed with the coarse-ground pepper, adding so much that the chicken could almost be called au poivre. The gentle heat of the pepper pairs well with the farmhouse fixings that make up a family-style dinner: coleslaw, green beans, and mashed potatoes with gravy. With Midwestern frugality, the kitchen serves each bird in ten pieces, including the back and ribs.

Owner Ginger Saccomando’s parents opened Wagner’s Village Inn in 1968. According to Saccomando, the roots of the signature recipe run even deeper. Her parents learned to fry chicken from the owners of the Hearthstone in Metamora, a now-closed restaurant that she says pioneered the regional fried chicken style.

Leave a Reply