This is excerpted from Ari Weinzweig’s newsletter called “Ari’s Top 5.” I met Ari years ago at a Southern Foodways Alliance symposium. Ari is one of the most interesting dudes I know, and I’m envious as to how prolific he is. I’m sharing this article to my blog because I’ve been frequently asked about self-publishing.

| One Person’s Perspective on Self-Publishing |

| The joy of turning words into books |

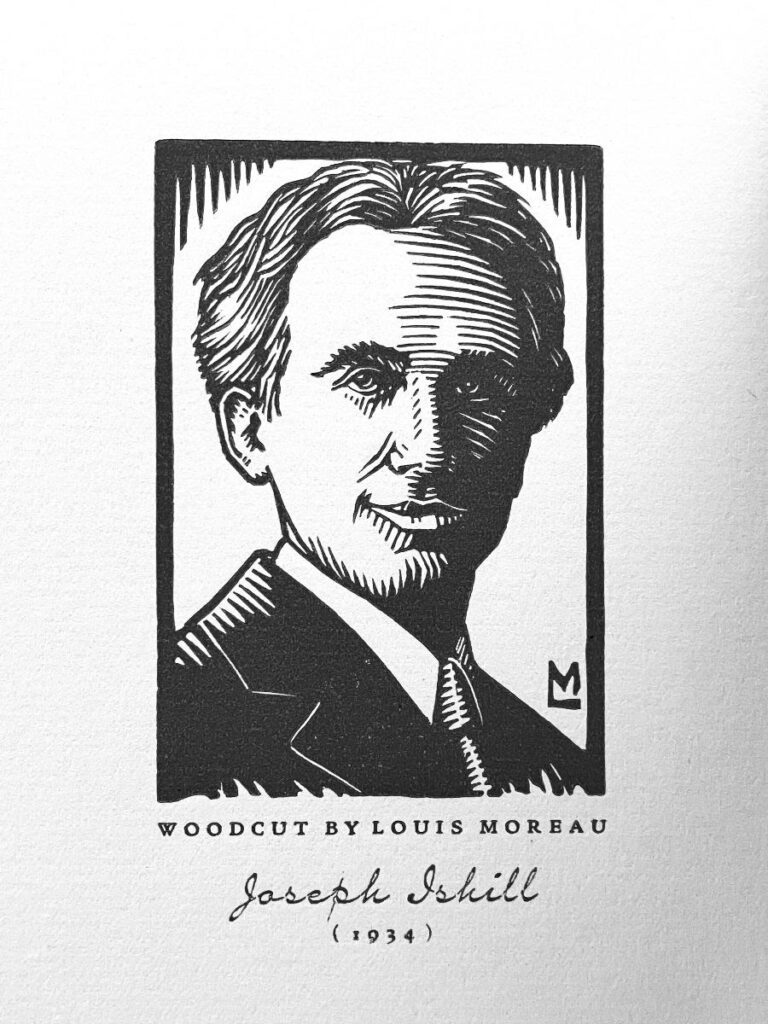

| The author Diane Ackerman, whose book A Natural History of the Senses had a big influence on my own sensory awareness and appreciation back when it came out in 1990, says that books, “capture the soul of a people, they explore and celebrate all it means to be human.” Working as I am right now—in tandem with the terrific Jenny Tubbs—to try to finish my next pamphlet, Ackerman’s statement got me thinking. The new publication is entitled “A Taste of Zingerman’s Food Philosophy: Forty Years of Mindful Cooking and Eating” and will be out, we hope, sometime later this month. I will write more in the coming weeks about its contents. Here though, in the piece that follows, I’m sharing a bit about the process of making the actual pamphlet—the work of turning what I’ve written in electronic docs into something tangible you can hold in your hands. Something that I hope brings both good learning and visual harmony in the way it looks and feels, engages both your emotions and your intellect, and adds some insight and understanding that can help you navigate the world. If we do our work well, we will create a practical piece of artwork that will bring a small bit of physical, emotional, and intellectual beauty to the world. Rick Rubin, whose new book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being I referenced last week and which continues to both inform and inspire as I read, certainly fills that bill for me. The writing resonates. I love the cover design. I like the way the type is placed on the page. I like how it feels when I lift it off the table. In the book, Rubin recommends that we:Create an environment where you’re free to express what you’re afraid to express.This is true, for sure, of our workplaces. It’s true in any healthy relationship in which we make ourselves vulnerable. It’s certainly true for me with every piece I publish. I am always anxious to share, but thanks to the encouragement of friends and colleagues, the creative and supportive work of Jenny Tubbs and L.J. Hard who do the behind-the-scenes work to help craft this weekly newsletter into something coherent, and regular rounds of encouragement from people like you who read it, I’ve taught myself to say things here that I’m not all that comfortable sharing. That sort of anxiety and awkwardness is something that nearly everyone I know who’s putting part of their artistic expression into the world experiences. When we push through that uncertainty and share our art, from the heart—work that is holistically true to who we are—I’ve learned that good things will nearly always come from it. That “art,” as I wrote in “The Art of Business,” could be anything from accounting to anthropology to flower arranging or philosophy. In this case, it’s the making of books and pamphlets. It’s also, always, about us, the people who make it. As Rubin says,No matter what tools you create, the true instrument is you. And through that you, the universe that surrounds us all comes into focus.In the spirit of all that, I thought it would be worth taking time to share more of why I/we have opted to make books and pamphlets as we do, in ways that are very different from what’s done in the mainstream publishing world. My hope in doing so is to encourage others to consider embracing comparably different, possibly more purposeful and more meaningful, routes to bring what you do, your “art,” into the world. Taking ideas and turning them into something tangible in creative ways that may not be what others do, but are nevertheless congruent with what you hold in your heart. I agree with Rubin:The imagination has no limits. The physical world does. The work exists in both.Books, for me, are far more than just the words. The weight of the book when I hold it, how the words appear on the page, where the paragraph breaks fall, which snippets should be sidebars, the color of the cover, the font that we use, the size of the lettering in the headlines, and Ian Nagy’s inspiring scratchboard illustrations. All are part of the experience of the books we make, and all, I believe, matter enormously. Yes, of course, the content, the words I write, are where it all begins, but the rest of the book (or in the current moment, the pamphlet) is really important to me, too. Neil Gaiman, another writer whose work I admire and whose books I appreciate, says,A writer can fit a whole world inside a book. You can go there. You can learn things while you are away. You can bring them back to the world you normally live in. You can look out of another person’s eyes, think their thoughts, care about what they care about.When you purchase a pamphlet or a book from Zingerman’s Press, my hope is that you will have a tangible piece of my words, of the Zingerman’s world, and of Jenny Tubbs’ sense of craft and creativity, something to read, to take notes in, to learn from and as Gaiman suggests, to take back to world where you normally live. While the rest of our food and drink is designed to be consumed and finished relatively quickly, the books—and their contents—are made to last. It is my hope (in part thanks to the construct of the Zingerman’s Perpetual Purpose Trust) that when the ZCoB hits its 100th anniversary in 2082, even though Paul and I will be long gone, the legacy and the learning that’s in the books and pamphlets will continue to contribute to the work of progressive leaders and learners all over the world. The thought to write about all this here, to share the process behind the pamphlet, came up for me just last week. Sitting outside on the bench in front of ZingTrain, on one of the remarkably warm sunny days we’ve had in southeast Michigan this winter, I was with Jenny, working on the soon-to-released new pamphlet. Jenny has been in the ZCoB for nearly 25 years now. For the last 15 years, most of her work has been to be the behind-the-scenes person who makes Zingerman’s Press possible. While I write pretty much all of the words that go into the books and pamphlets we produce, it’s Jenny who caringly and creatively works to wrangle what I’ve written into print in such a beautiful way. Jenny is, in the best possible way, exceptionally good at what she does, and is to me the epitome of what it would mean to be a “Jill of all trades”—as Wikipedia defines it, “A woman competent in many endeavors rather than only one.” She doesn’t just make books and pamphlets; she paints, she makes pottery, she plays the banjo, she’s one of the facilitators for the ZCoB Huddle, she’s a guide on our Food Tours to Spain, she’s on our Great Service Group, and she teaches our internal visioning class. At Zingerman’s Press, Jenny does a whole range of diverse tasks that help bring our books to fruition. She edits, lays out, contributes caring input, expresses concerns, offers creative solutions, and actively engages in the sort of healthy back-and-forth conversations (even the awkward ones) that it takes, I think, to make something great happen in a collaborative way. Without Jenny’s work, what you’re reading here in this enews would not exist as it does, nor would any of the books or pamphlets. Not only does she do all that, she also packs your Zingerman’s Press orders and gets them in the post so you can read them! Many of you who have ordered books from Zingerman’s Press will have benefitted from the creative world-class “craft service” she gives to many of our book-buying clients. The small handwritten notes, her willingness (actually, eagerness) to take an extra minute or two to hand-wrap books and write a thank-you message to go with them have brought joy to many around the country and around the world. Her combination of creative acumen and hands-on ability is, in my experience, rare, and is also integral to what we do to make these books and pamphlets possible. Rick Rubin writes:One of the greatest rewards of making art is our ability to share it. Even if there is no audience to receive it, we build the muscle of making something and putting it out into the world. Finishing our work is a good habit to develop. It boosts confidence. Despite our insecurities, the more times we can bring ourselves to release our work, the less weight insecurity has. What caught my attention that afternoon, though, was realizing that although I might not have said it out loud to too many people, that part of the work brings me as much joy as the writing. Yes, the writing is wonderful, and I have come to love the craft of it. At the same time, I was reminded the other day while sitting in the sun working on the bench, that the other parts of making the pamphlets and books—always in tandem with Jenny Tubbs—are just as rewarding. It’s not, I know, for everyone, but for me, it’s meaningfully creative work that I care about deeply. My sense of it fits well with what Rick Rubin writes: “We’re called to … put our faith in the curious energy drawing us down the path.” The industrial world has taught us to isolate and separate in the interest of efficiency. The approach we take with Zingerman’s Press is the opposite. We have adopted a holistic way of working that I’ve come to see as the “farm-to-table version of making books.” In much the same way that my girlfriend/life partner/co-adventurer Tammie Gilfoyle is currently starting the propagation of the new season’s seeds at Tamchop Farm and will go on in the coming months to do everything from getting them replanted to caring for them, weeding, hand-watering harvesting, selling, and also cooking and eating what she grows in our kitchen … that’s the metaphorical equivalent of what happens to make the words I write into the books and pamphlets that Zingerman’s Press produces. The actual printing is done by a company we work with in Ann Arbor, but the rest of the book-making process is all done here in the ZCoB. What follows is the story of how that happened, why it matters so much to me, and why, although it’s certainly more work for us to do it this way, I’m enamored of the process now more than ever. About 25 years ago, I did some work with the big publishing world. Two books I authored were released that way. The books were perfectly fine and they sold plenty well, but I didn’t take joy from the work of making them, nor, really, from the finished books. The whole experience gave me a new understanding of musicians who would say something like, “We lost control of the music to the label. The record they put out isn’t really how we hear the music in our heads.” I didn’t like that experience and I didn’t want to have it again. All of which pushed me to take on the additional work of putting books together here, in-house, ourselves. We have been doing our own books—what most of the world refers to as “self-publishing”—ever since. It is possible, I know and say with great gratitude, only because of Jenny Tubbs’ wonderful work, and Ian Nagy’s amazing illustrations, because I’m part of the Zingerman’s Community, because of ZingTrain, and because I keynote at large conferences where we can sell books direct to folks who are interested. Five books, dozens of pamphlets, 297 editions of “Zingerman’s News,” and many hundreds of these e-newsletters later, I truly do enjoy the work of proofing, figuring out the right layout, picking colors, and crafting what goes to print as much as I like writing what appears on the pages. Often when I tell people that we self-publish, their immediate response is something like, “That’s smart! The margins are way better that way.” I smile every time, because although I’m not honestly sure if the margins are better (there are a LOT of peripheral costs and it takes a lot of time to do it), the drive to work this way was not, and is not, about finances. I agree fully with Rick Rubin when he says, “commercial considerations usually get in the way.” Yes, of course, I/we need to make a living. But money has never been the inspiration, nor the driving force behind any of the work we do—especially not the idea of doing the books and pamphlets the way we do them. If profit was the point, we would do this very differently. The decision to self-publish was not because we couldn’t find someone to publish the books, but rather out of a commitment to authentic art, effective self-expression, and bookmaking as a creative act. There are three main things that drive me to work this way:1. Connection. Big publishing certainly has its upsides. Many of my good friends release their books that way, and the industry has some wonderful people working in it. My experience of it, though, was less than positive. I was frustrated by its application of the Industrial Age idea that separation and specialization are a more efficient way to work. In the big publishing world, I wasn’t allowed to talk to anyone involved in the project other than the editor and the PR person. Here, with Zingerman’s Press, we can work on the whole thing together, moving back and forth from content to color choices, pagination to paragraph breaks in the understanding that each element of the book is actually impacting, and impacted by, the others.2. The creative act of collaboration. Putting together a book, or pamphlet, requires a LOT of back and forth between me and Jenny, with input and help from a host of others. Last-minute insights inevitably appear. Each project presents a plethora of surprises and unexpected struggles and leaves us every time with a new grasp of nuances. Rick Rubin says,The work reveals itself as you go. … It’s impossible to know until you see the group and then you understand what’s important. … You only know that in the context of seeing them all.Which is exactly what I find over and over again. When I see the first layout—on real paper—it always looks different than in my head or on the computer screen. Doing the work this way nearly always leads me to alter what I’ve written, which changes the layout, which leads me to understand things in new ways that help me to improve the content. What you read when you get this new pamphlet will have evolved a lot since Jenny and I sat together on the bench last week. Small shifts that come from this part of the work, I believe, are part of the art. 3. Positive relationships. With all due respect to Amazon (and I have many friends who sell their stuff that way for very good reasons), I want to work—applying what I’ve learned from Emma Goldman and other anarchists—so that the means we use to make and sell the books will be consistently congruent with the ends we want to achieve. Selling books about progressive leadership and creative, locally-focused small business via the anonymity of the world’s biggest distributor just doesn’t make sense for me. I freely trade off increased sales to get more opportunities for interaction. I love having the connection to folks who order the books and pamphlets, and Jenny does a remarkable job of making their purchases into exceptional experiences. Our definition of local, detailed in Part 1, Secret #16, is more about our relationships with the people we buy from and sell to than it is about geography. Working this way has helped to make that happen. Instead of anonymity, we have an anarchistic sort of direct action—there’s much less middleman involvement. Every week I interact—online or in person—with someone who is reading the books and a wealth of wonderful things have come from those connections. To be clear, what we do here at Zingerman’s Press is not necessarily what everyone else should do. This way works well for me, but it might, I understand, be miserable for you. The Zingerman’s Bakehouse book came out great and Amy and Frank worked on it with Chronicle Books. There is a new Bakehouse book coming out with the same publisher this fall, entitled Celebrate Every Day: A Year’s Worth of Favorite Recipes for Festive Occasions, Big and Small. The early mockups Chronicle has sent look terrific. It’s not that one way is “wrong” and the other “right.” Rick Rubin’s beautiful book, for example, was published by Penguin. Rather, in the spirit of the new pamphlet, the decision to run Zingerman’s Press as we do is more about philosophy, about vision, and values, about working with what we love to work with in ways that work for us. Joseph Ishill’s legacy is not what pushed me to self-publish, but the many books and pamphlets he made—all by hand—over the course of his life serve as an ongoing inspiration. Ishill was born on the 11th of February, 1888, into a Jewish farming family in the commune of Botosani, in the northeast corner of Romania, not far from the modern-day borders with both Ukraine and Moldova. In 1902, at the age of 14, Ishill’s parents apprenticed him to a local typesetter, which is where he began to learn what became his lifelong profession. That same year, Ishill read Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, which had a big impact on his thinking. He later moved to the capital city of Bucharest, where he began to learn about anarchism. In 1909, at the age of 21, Ishill made the bold decision to depart for a freer and more rewarding life in the U.S. After arriving in New York City, Ishill found a job doing the typesetting and printing work he’d learned in his youth. In 1915, at the age of 27, he moved to the anarchist Stelton Colony in New Jersey, which had been originally named for the executed Catalan anarchist Francisco Ferrer. Two years later, he met the poet Rose Freeman and the two married and had three children. He and his wife went on to start Oriole Press (named for the oriole he saw outside the window of his workshop), the moniker under which most of his 200-plus pamphlets and books were published, in a cottage behind their home in Berkeley Hills, New Jersey. As Ishill wrote, “I began to see the world of my recognizable dreams. I had found my vocation.” |

|

| With Rose’s assistance, Ishill selected and edited the essays, poems, letters, illustrations, woodcuts, and art that would be included in each of his publications. He printed them on his own press and assembled them all himself. The two volumes of Free Vistas he produced—the first from 1933, which is having its 90th anniversary this year, and the next in 1937—are truly some of the most beautiful books I’ve ever seen. They’re very definitely about anarchism and free thinking, but they’re also incredible works of art. Each was printed, by hand, in very limited editions—less than 300 copies—on probably a dozen papers of different textures, colors, and sizes. They include beautiful woodcuts from artists Louis Moreau and John Buckland Wright, writings from people like Emma Goldman, Peter Kropotkin, and Walt Whitman; and poetry, including that of his wife, Rose Freeman Ishill (I treasure my copy of the beautiful boxed set that Ishill did of her poetry). To say the books are amazing is an understatement. In over half a century of printing, Ishill probably never made much money from the books and pamphlets. To pay his bills, he had a day job as a printer in a bigger shop in the City. Many of his books—some of which took years to put together—were simply gifted to friends and various thought-leaders by whom he was inspired. Ishill was widely respected in the anarchist community and he was a generous teacher—historian Paul Avrich’s amazing oral history, Anarchist Voices, includes many folks remembering that Ishill taught them to print. Kathy Ferguson, who has a great new book on the impact of anarchist printers, Letterpress Revolution, quotes Thomas A. La Porte of the University of Michigan Special Collections Library, who notes that Ishill, “has been lauded both by radicals, who recognize him for his efforts in publishing radical materials, and by fine press enthusiasts, who consider him to be one of the finest American printers and typographers of the twentieth century.” I feel fortunate to have found and bought copies of many of Ishill’s books and pamphlets over the years. They are now nearly a century old, but their beauty is still fully intact. The words inside are informative, wise, and wonderful. The art is exceptional. And they give me enormous joy every time I pick one of them up. Ishill didn’t just make beautiful books, he lived a life to which I feel philosophically drawn. He was very engaged with anarchist belief systems and worked hard to weave them into what he did every day, writing (in the memorial book he created for anarchist geographer, Élisée Reclus), “It is first necessary to possess one’s own self, to revolve around one’s own axis which must radiate ideals and not mechanical reproductions of a pattern designed for millions of duplicates.” Joseph Ishill passed away on March 14, 1966, which means that the anniversary of his passing comes next week, one day before Zingerman’s 41st anniversary. After his death, his daughter, Crystal Ishill Mendelsohn, wrote:Although Ishill was highly praised for the artistry of his typography by connoisseurs here and abroad, his conviction was that the text was always the most important aspect of a book and that all the other elements must be harmonious—the physical working with spiritual. That in essence is what Joseph Ishill was all about.It’s also, I hope, what the books and pamphlets we put out at Zingerman’s Press are all about as well! As I’ve learned over all these years of working this way, the books we make are never really “done,” they just go to print. That will be the case with this new pamphlet, too. Everything we publish—including this new piece—is imperfect. No matter how many proofs are done by professionals, Jenny and I know now that we will almost always find a typo within two days of release. We both used to get really upset. Now we mostly just laugh. The imperfection is part of the art, the same way that Tammie’s exceptionally flavorful tomatoes may have cracks or blemishes that would never pass muster in mass market distribution. I hope, with all my heart, that what we produce here will have a positive impact. Books make a difference in the world. And, to my view, what Joseph Ishill wrote a century ago still stands:Until the dawn of a more luminous day, let at least the few in quest of truth and beauty find their need of content in the written word. Nothing, alas, in this era of harsh reality can quite take the place of books.What I’ve written here is about my relationship with the making of the books and pamphlets we publish. The odds are that your profession and/or your passion lie in other areas, but the idea of engaging with our work in new and different ways, I believe, can be universal. That when we embrace what we make in its holistic entirety, when we work in ways that are well aligned with our passions and our principles, when we focus on purpose before profit, when we work to make a living while in the process helping others to live better lives, good things are highly likely to happen. My hope here is really just to encourage everyone who’s interested to examine norms and be ready to reshape the generally accepted-by-the-world ways of doing things in the interest of finding—actually, creating—their own positive path. Rick Rubin writes that:The artists who define each generation are generally the ones who live outside of these boundaries. Not the artists who embody the beliefs and conventions of their time, but the ones who transcend them. … [people whose work] widens the audience’s reality, allowing them to glimpse life through a different window. Joseph Ishill was one of those people. These lines that he wrote nearly a hundred years ago inspire me every time I read them: I wish always to live my own life and by myself to create things which appeal to my taste. I am bound to confess that this is a hard road but it is an honest one and I propose to end my days in this manner. |

| P.S. The visioning process is one of the best ways I’ve ever experienced to tap into much greater clarity about the future we hold in our hearts! Check out ZingTrain’s virtual session later this month, or the Visioning Pamphlet Bundle Jenny put together at Zingerman’s Press. P.P.S. At Letterpress Publishing, Michael Coughlin continues the tradition of anarchist printers of which Joseph Ishill was such a positive and prominent part. All his work is wonderful, including this pamphlet that reproduces the Introduction Ishill wrote for the beautiful book he crafted in memory of Peter Kropotkin. He also prints the covers for “The Art of Business” for us. P.P.P.S. Check out our Letterpress Notecards—featuring our iconic Delicatessen—hand drawn using a traditional scratchboard art technique by Ian Nagy. (You can read an interview with Ian about the process in Part 2.) Each card is letterpress printed locally, by hand, on an antique printing press by our friends at Paper & Honey, and accompanied by French Paper envelopes made in Niles, Michigan. |

Is there a way to follow you? I just listened to yo being interviewed pish today’s episode of PushBlack Black History Year!

Did you enjoy the episode? I’m interested in finding great soul food near me in Fall River MA. Very close to Providence RI. I have always wanted to venture into Roxbury Boston and try some restaurants there. But, the crime rate is ao high there I’m concerned for my welfarewlfare. Hate to say it, but especially as a white man. I wish they had an explore Roxbury group or something so people could explore the area without concern. Also, I’ve been watching and reading about Africa town in Alabama. I can’t wait to check it out! Boston has “China town, “the Italian North end. Why not an Africa Town? where people are proud of there heritage and welcoming to outsiders and have top notch restraints like the other two highly cultural parts of the city?! I would love to see that! I got my engineering degree right next door at Northeastern, and would constantly look at Roxbury and wish I could walk around there and find some restaurants that I love and bring my friends and out of town guests there. But, they always want to go to the North end. I wish Roxbury could make a name for itself as a place people want to go for great food, and a great cultural experience❣️

Thanks so much for your note! Sorry that it’s taken a minute to respond. I’m active on social media on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. I’m The Soul Food Scholar on every platform, my handle is @soulfoodscholar.