Earlier this week, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick debuted their ten-part documentary The Vietnam War. A documentary of such magnitude couldn’t cover every single story, and here’s one that fascinates me: the presence of soul food restaurants in southeast Asia during the Vietnam War era. These joints proliferated all over that region of the world, and they were often operated by African American military veterans. Local entrepreneurs sometimes got in on the soul food act as well. I wrote about this tasty phenomenon in the chitlins (a.k.a. chitterlings, a.k.a. pig intestines) chapter of my book Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. Here’s an excerpt:

Some African American veterans opted to stay in Asia during the military conflicts of the 1950s and 1960s, and some even opened up soul food joints. No surprise, these places often featured chitlins.

In April 1973, Bob Adams, an Air Force staff sergeant (E5) stationed at Yokota Air Force Base in Japan, wanted to make some chitlins. He remembers chitlins were available at the base’s commissary in two U.S. brands, Swift and Hormel, with one in a red pail and the other in a yellow pail. Though Adams can’t recall which one he chose, he remembers that one brand had the reputation for being “cleaner,” so he purchased that one.

Actually, Adams could have gotten his chitlins from local sources. Asian food cultures have much of the same culinary vocabulary as soul food: fiery hot condiments, fish, leafy greens, rice, sweet potatoes, and funky parts of chickens, cows, and pigs–all are on the menu along with chitlins. From the 1960s until the late 1980s, following the Vietnam War, soul food joints run by black military veterans were popping up all over Asia.

In April 1970, air force master sergeant Allen A. Rious opened up the BP Club on the outskirts of Yokohama, Japan. The entire time the club was in business, there was controversy about whether the BP stood for “Beautiful People” as Rious claimed, or “Black Power” as the Japanese cops suspected. The BP Club welcomed lots of famous visitors. Muhammad Ali stopped by after he fought Mac Foster in Tokyo on 1 April 1972.

Soul food spots also popped up in Bangkok, Thailand, like Jack’s American Star Bar Bangkok (which was fictionally depicted as a restaurant called Soul Brothers in the 2007 film American Gangster). The soul food business was so good even the locals got in on the act and opened up restaurants that catered to black servicemen. Army sergeant Leon A. Casey recalled visiting a restaurant near the Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base in Vietnam in the early 1970s. He dined on chitlins, black-eyed peas, collards, and a Vietnamese version of cornbread, all washed down with a local beer while Lou Rawls crooned from a record player. As he left, the Cambodian owner implored him to tell all of his GI buddies about the place.

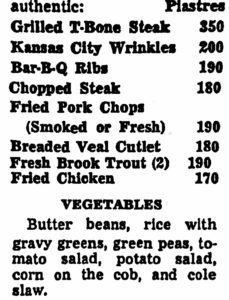

The L&M Guest House, located on Coathang Street in the heart of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) quickly established itself as Vietnam’s most popular soul food restaurant. In a familiar pattern, Andrew Mitchell, a former merchant marine steward and New Yorker, opened up the L&M after he fell in love with a Vietnamese woman and settled in Saigon in 1966. A Washington Post correspondent visited the L&M in 1967 and described the scene: “Except for the petite Vietnamese woman who glided silently by putting plates of fragrant barbequed spareribs or steaming platters of chitterlings on the huge table in the middle of the room, everybody in the place was Negro.” The correspondent added that on that day, L&M’s “‘Menu Pour Le Jour’ features Kansas City Wrinkles, Bar-B-Q Ribs, Fried Brook Trout, Fried Chicken, butter beans, rice with gravy, greens.”

Once again, chitlins were a star attraction, and Mitchell explained emphatically in a newspaper interview why chitlins were such a big draw: “‘Sometimes I buy 180 pounds of chitterlings [Kansas City Wrinkles] a week, pigs feet, hog maws–they’re easy to get over here because the Vietnamese eat them too. . . . A lot of the fellows over here get a little lonely’ Mitch said. ‘And when you’re down and out and thinking about home there ain’t nothing like some chitterlings, potato salad and greens to make you feel better.'” Homesick GIs frequently redefined the places they ended up in to make them like home. The Khanh Hoi neighborhood immediately surrounding L&M Guest House was called “Soulsville,” and darker-skinned Asian women were called “Soul sisters.” On the flip side, Vietnamese people often called black soldiers “souls.” If you were a good lover, Vietnamese women might call you a “soul one.”

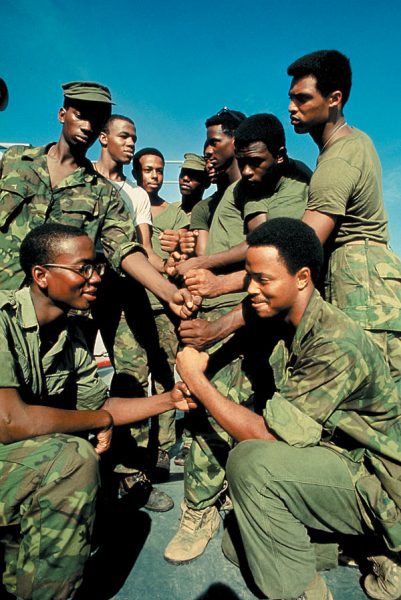

Regardless of where these soul food joints took root, the restaurant experience was about getting together with the other brothers. In a New York Times interview on why he frequented the Saigon soul food places, one black soldier said, “Look, you’ve proven your point when you go out and work and soldier with Chuck all day. It’s like you went to the Crusades and now you’re back relaxing around the Round Table–ain’t no need bringing the dragon home with you.” The soul food restaurants became a place where black soldiers could “get away from ‘the man'” and “luxuriate in blackness” or “get the black view.”

—

Do you know a Vietnam veteran? Please ask her or him if they remember any of the soul food restaurants in southeast Asia during that time. If so, I would love to speak with them! I’ll post soon on how red drink flowed in Vietnam.

The Soul Food restaurant referenced in the book was known by me as “Nams”, the restaurant was owned and operated in 1969 – 1970 during my tour of duty in Vietnam 🇻🇳 by the wife of an Airforce NCO who, for reasons I cannot recall had to leave Vietnam and take up residence in Thailand, his wife took enough money to him so that he could open a Soul Food restaurant in Thailand.

This is fantastic! Thanks for the follow-up. Do you remember some of your favorite dishes at Nams?